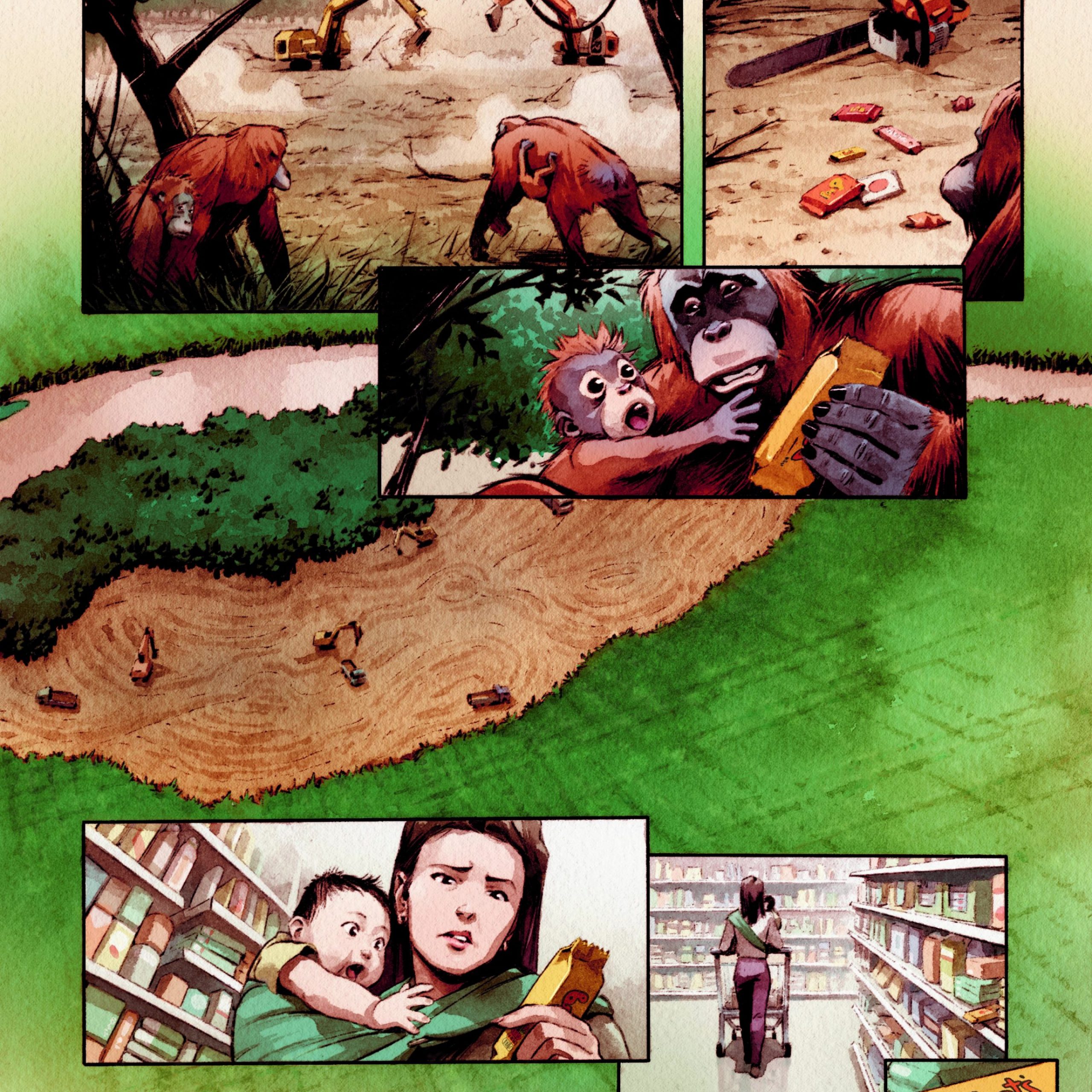

Rewriting Extinction-Stories to Save Our World, a campaign using comics to raise money and awareness for projects to tackle BOTH the biodiversity and the climate crisis, has launched two comics drawing attention the the plight of orangutans due to deforestation. Working with Orangutan Land Trust, they are calling for consumers to demand sustainable palm oil in order to save orangutans.

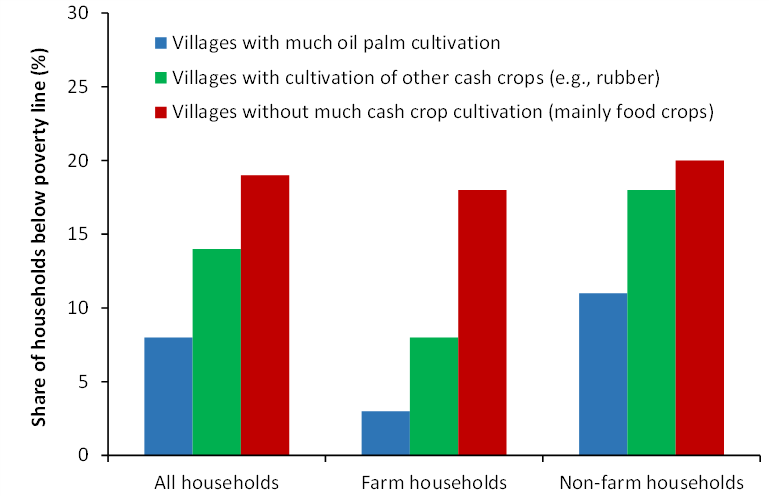

This message goes to the heart of why conservationists see sustainable palm oil as critical for the survival of the orangutan as well as for the planet in general.

Orangutan Land Trust:

“The single-most important thing we can all do to save orangutans is demand sustainable palm oil.”

The organisations and experts that lead the way in protecting orangutans share this belief. Orangutan Land Trust have been at the forefront of driving sustainability in the industry for over a decade. Their President and Co-Founder is Lone Droscher-Nielsen, famously featured in many documentaries and series over the years including Orangutan Island and Orangutan Jungle School. Lone, knighted in her native Denmark for her services to wildlife, created the Nyaru Menteng Orangutan Rehabilitation Project in Indonesian Borneo. It is now the world’s largest primate rescue project, and has set the standard for orangutan rescue, rehabilitation and reintroduction. Lone herself has saved hundreds of orangutans.

“Many of the orangutans we have saved have come as victims from the unsustainable expansion of oil palm across Central Kalimantan over the past few decades,” she explains. “We’ve rescued orangutans starving and ill because their forest habitat has been cut or burnt down, as well as those suffering from horrifying injuries as the result of conflicts with humans when they go in search of food in villages and farms. Most of the orphaned infants at the project represent the “lucky” few who survived, but whose mothers did not in such conflicts.”

“We designed the centre in 1998 to accommodate up to 100 orangutans. When in the early 2000s, we were bursting at the seams with many hundreds of animals, we realised we really needed to do something to stem the tide of incoming victims; we needed to stop the orangutans getting displaced or harmed in the first place. So we decided to look deeper at what could be done with the palm oil industry itself. From engaging with plantation managers to use Better Management Practice, to working with multiple stakeholders in platforms like RSPO, we were determined we would see the way palm oil was being produced changed to one that doesn’t harm orangutans and their rainforest habitat. These efforts actually protect orangutan lives. It’s because conventional palm oil is catastrophic to orangutans & forests, that choosing sustainable palm oil is critical for their survival. The single-most important thing we can all do to save orangutans is demand sustainable palm oil.”

Orangutan Veterinary Aid: Treating orangutan victims of unsustainable oil palm

Another organisation that has witnessed the impact of unsustainable production of palm oil on orangutans is Orangutan Veterinary Aid. This UK-based organisation supports the veterinary teams at orangutan rescue centres across Borneo and Sumatra, providing equipment, training and hands-on assistance. Its Director, Dr Nigel Hicks shares his viewpoint: “Working with the vet teams at the front line of orangutan rescue we regularly have to deal with orangutans severely traumatised both physically and mentally. The rescue centres are constantly working with local communities and neighbouring plantation owners in an attempt to educate and to protect orangutans and those plantations signed up to regulation and sustainable production have a commitment to protect orangutans found on their land.

“The multi-billion dollar palm oil industry is not going to disappear so it is essential that we engage in dialogue with the industry in an attempt to reduce deforestation and preserve the orangutans. Engaging with companies to engender respect for orangutan and to develop corridors to facilitate the movement of individuals is needed together with exploring options for commercial interests to continue to support their country’s economy whilst avoiding the destruction of virgin forest and adopting a more sustainable ethic. All of these will benefit wildlife, indigenous forest-dwelling communities and our climate whilst saving orangutans by preserving their forest habitat. This means we are automatically making the necessary changes to protect our world. Everyone though, must play a part. Making concerted efforts as individuals to reduce our overall palm oil consumption and seeking products sourced sustainably is an essential task which we must all address with great urgency if we are to bring about change.”

Hutan:

“Embracing sustainable practices will go a long way to sustain orangutans who are living outside of protected forests.”

In Sabah on the Malaysian part of Borneo, conservationists at the NGO Hutan have been studying orangutans, elephants and other wildlife in the Kinabatangan floodplain for decades. As populations of these species became more and more fragmented due to oil palm cultivation and other activities, strategies to protect the increasingly vulnerable animals have been implemented. Dr Marc Ancrenaz, Scientific Director of Hutan explains:

“Our observations in Sabah show that orangutans are using the oil palm dominated landscapes where the animals live. As such, it is crucial to support the best exploitation practices and keep trees within the plantations. Orangutans are more adaptive than we thought: today they are found in agricultural landscapes and everything must be done to sustain the individuals who survive there. Embracing sustainable practices will go a long way to sustain orangutans who are living outside of protected forests. As such we need to design new ways for people and orangutans to coexist in the Anthropocene.”

Borneo Futures: Science-based interventions for conservation

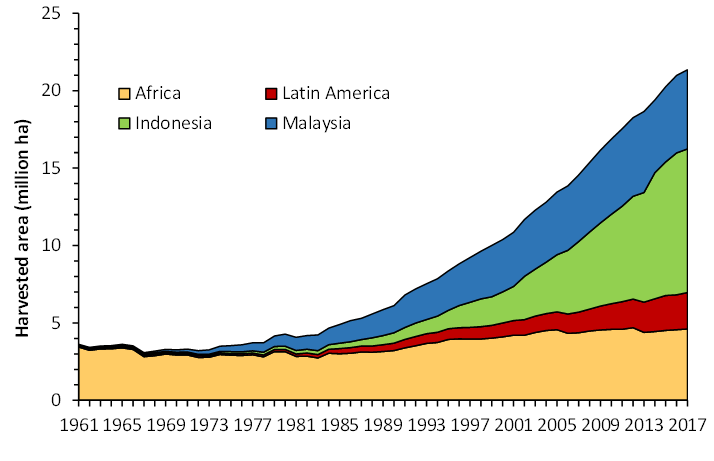

Dr Ancrenaz is also a Co-Director of Borneo Futures, along with Dr Erik Meijaard. Borneo Futures engages with projects focused on innovative science that informs the practices and policies of environmental management in tropical forest areas. Dr Meijaard also leads the IUCN Oil Palm Sustainability Taskforce. In an interview with the BBC News Dr Meijaard said, “Orangutans are a lowland species on Borneo and Sumatra and that’s where palm oil is grown. The two often clash, palm oil displaces orangutans, they are pushed into gardens where they generate conflicts with locals and that’s where you get these killings. Orangutans are incredibly versatile, but what an orangutan can’t deal with is killing. Because they are such slow breeding species, the killing has a really big impact.”

But he warns against a blanket boycott of palm oil. “If palm oil didn’t exist you would still have the same global demand for vegetable oil. If you stop producing palm, other oils will have to be produced somewhere else. So instead of harming orangutans you’ll be harming bears or jaguars, it just pushes the problem somewhere else because the demand for those oils will still be there.”

Gunung Palung Orangutan Conservation Program: Community-based conservation

The Gunung Palung Orangutan Conservation Program is a research centre in West Kalimantan which engages in community-based conservation. As signatories to the Statement in Support of Sustainable Palm Oil signed by close to 100 conservation organisations around the world, GPOCP hold out hope for the orangutan: “There is hope for the remaining orangutan populations in Borneo and Sumatra, but we will only be successful with contributions from every stakeholder: NGOs, local communities, scientific researchers, local, national and international governments, and conservation-minded individuals.”

Orangutan Conservancy:

“Palm oil does not need to destroy more forests in conversions and in concessions.”

The Orangutan Conservancy is dedicated to the protection of orangutans in their natural habitat through wild research, capacity building, education and public awareness programs, and by supporting numerous on-the-ground efforts to save South East Asia’s only great ape. They, too, support sustainable palm oil.

“Here at the Orangutan Conservancy we are well aware of the damage that is done because of greed and the desire for more and more palm oil – we also recognize that it is not entirely the country of production’s fault as the highest demands for oil palm products come from outside and from highly developed nations and the fight needs to begin there not in the developing nations where oil palm production begins. As palm oil is a product that is very ingrained in many products, we understand that it can not be eliminated entirely, but it certainly does not need to destroy more forests in conversions and in concessions.”

Sumatran Orangutan Society:

“We need to demand an end to deforestation to ensure safe habitat for orangutans and all the other species that also rely on the rainforest.”

The Sumatran Orangutan Society has long advocated for sustainable palm oil. When asked, “Should we boycott palm oil?” SOS replies, “This is a question that each individual consumer, and each company with palm oil in their supply chains, must answer for themselves. A business might eliminate palm oil from their products until they feel confident that their supply chain is deforestation-free. A shopper browsing the supermarket aisles might wish to send a message that they are aware of, and outraged by, the negative impacts of the palm oil industry by choosing palm-oil-free options. The question we encourage individuals and companies to consider is:

Will this action help orangutans, forests, and communities? The answer is an unequivocal no. What we need to do is ensure that it is cultivated in the least damaging way possible. Oil palm does not need to be grown at the expense of forests. Instead, we need to demand an end to deforestation to ensure safe habitat for orangutans and all the other species that also rely on the rainforest. The issues around palm oil (like most crops) are complicated and can’t be reduced to ‘it’s good’ or ‘it’s bad’. We are happy to see so many experts sharing their knowledge about sustainable palm oil and helping consumers make informed, wildlife-friendly choices.”

Paul Goodenough, the mastermind behind Rewriting Extinction, says,

“We hope the comics we share will result in people all around the world taking one simple action to make a change. By choosing sustainable palm oil, we can all make a difference for orangutans.”

Learn more about Rewriting Extinction here.

Credits:

Kinda a mess

Safely endangered

David Schneider

Amber Weedon

Paul Goodenough

Purchasing power

Paul Goodenough

Hector Trunnec