Palm oil-related deforestation declining in Indonesia: what is going on?

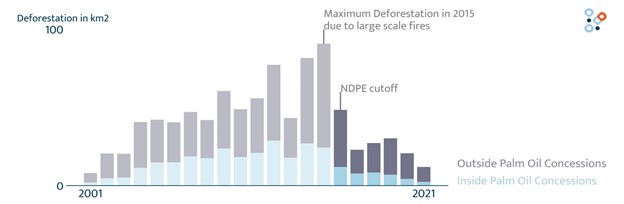

Indonesia is the world’s leading palm oil producer and exporter, and the Indonesian palm oil industry has often been accused of the number one cause of deforestation in that country in recent decades. However, the latest data shows that the tide is turning. In 2021, deforestation for oil-palm plantations in Indonesia and Malaysia was at its lowest level in 20 years, at less than 5% of the highest historical levels.

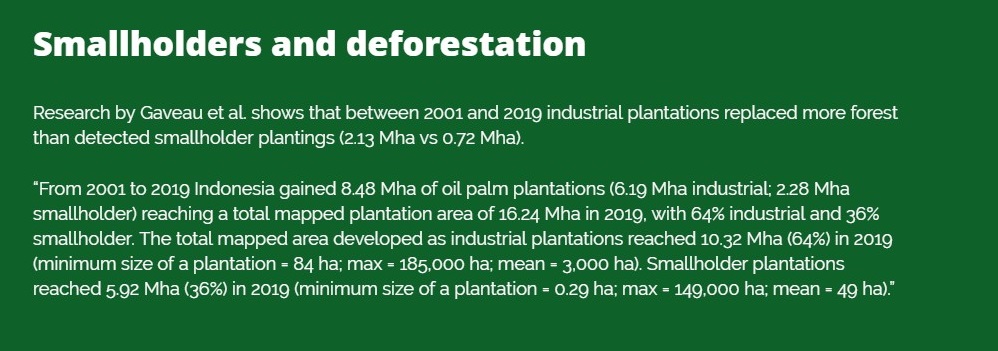

Source for the figure: Gaveau, David (2022, March), Nusantara Atlas. Based on a PLOS ONE publication in March 2022.

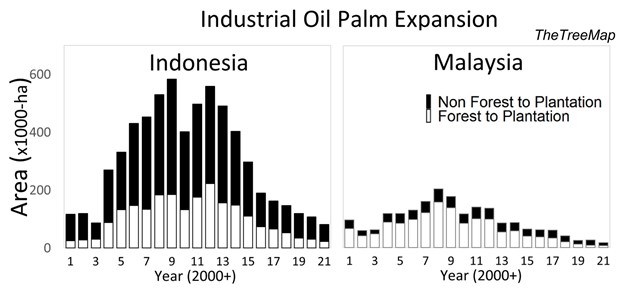

Environmental research organisation Tree Map analyzed the level of palm-driven deforestation. Based on this research, lead author David Gaveau concluded: “We estimate companies converted 22,000 ha and 6,600 ha of ‘primary’ forest to industrial oil palm in 2021 in Indonesia and Malaysian Borneo, respectively. Plantations expanded by 82,000 ha in Indonesia and by 17,000 ha in Sabah and Sarawak. The analysis includes all industrial plantations inside and outside concessions. Based on Landsat and Sentinel-2 Time-series.”

In a similar analysis, Chain Reaction Research concludes that in 2021, in Indonesia, Malaysia and Papua New Guinea combined, 19,000 hectares (ha) of forest and peat were cleared for oil-palm plantation development. This is the lowest level in 20 years.

These findings are confirmed by the research of Satelligence, which clearly links the decline in Indonesian palm oil-driven deforestation to the implementation of No Deforestation, Peat and Exploitation policies of palm oil buyers.

Source: Satelligence (2022, March), LinkedIn post.

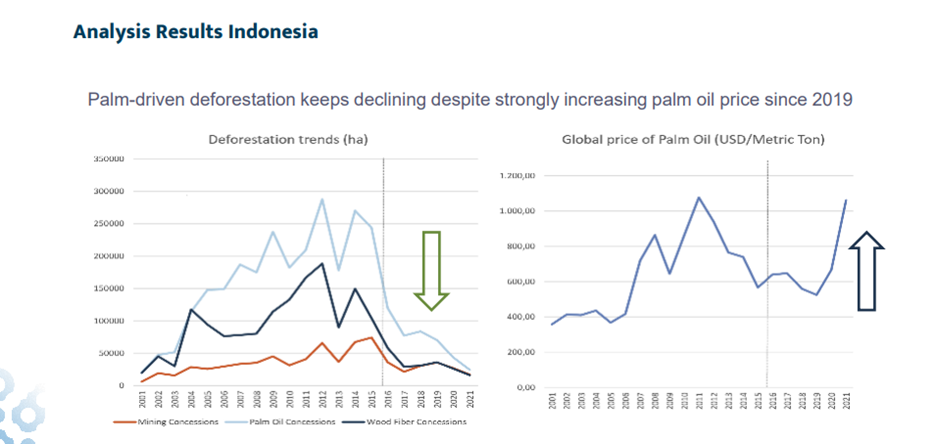

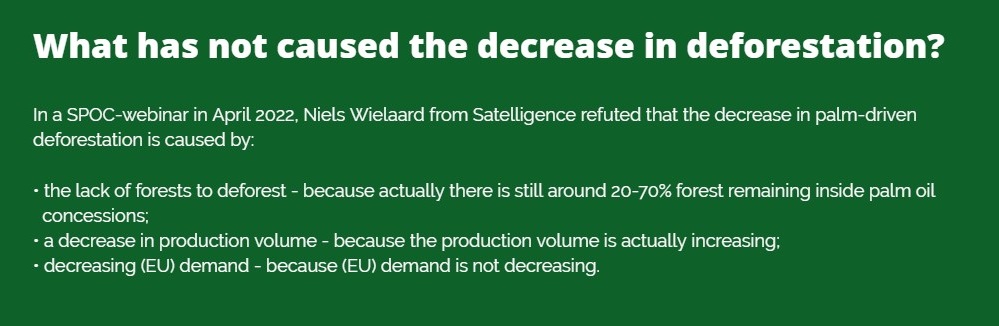

What is remarkable about this trend, is that it contradicts the well-known paradigm that high commodity prices equal high levels of deforestation. In 2021, prices were at their highest level since 2010 and this did not lead to increased deforestation. This is clearly visible in this Satelligence figure:

Source: Satelligence (2022, April), Presentation SPOC webinar The case of palm oil & the latest state of play in Indonesia and Malaysia.

So what are the reasons behind these trends?

While the trend is hopeful, it is not certain that the trend will continue. To ensure the level of deforestation continues to drop, it is important to better understand which factors have been instrumental in decreasing the destruction of forests for oil-palm plantations.

Many people have speculated about this. A general conclusion is that it is very difficult to pinpoint any intervention as decisive, but that many forces pushing in the same direction are making the difference. A 2019 study of the Tropical Forest Alliance and Daemeter concluded that “government, private sector and CSOs leveraged the policy environment to achieve impact on the ground“. The six main impact measures of progress and the six critical enablers of progress are represented by TFA and Daemeter in the following figure:

Source: TFA and Daemeter (2019), Decade of Progress: Reducing commodity driven deforestation in Indonesia and Malaysia: Areas of Progress, Drivers and Future priorities, p. 7.

Further research is needed to improve our understanding of what causes decreased deforestation, but in the wake of conclusive evidence, based on the TFA and Daemeter study and other sources, it is safe to say that the following interventions have played and are playing an important role:

- A variety of NGO groups have carried out relentless campaigns against the use of palm oil tainted with deforestation and social controversies. This “created a strong impact on the demand for crude palm oil, particularly in European Union nations”.

- The private sector has played its role via increased demand and uptake of sustainable and certified palm oil. More and more buyers have implemented No Deforestation, Peat and Exploitation policies and started buying 100% RSPO certified sustainable material (CSPO) for all types of palm oil used, including Crude Palm Oil (CPO), Palm Kernel Oil (PKO), Palm Kernel Expeller (PKE) and Palm Oil Derivatives (POD). This often covers the entire corporate group and all countries where the group operates. Chain Reaction Research noted that “none of the 10 largest deforesters in 2021 can be conclusively linked to the NDPE market. Two have links via Fresh Fruit Bunch supplies and minority shares in a mill”.

- In 2018, the RSPO strengthened its principles and criteria for certification with new requirements on deforestation and peatlands.

- Companies, like Unilever, have started to make an effort to move from buying certified material towards a supplier-based approach. In a supplier-based approach buyers try to not only clean up their own supply chain, but cooperate to clean up all supply chains of the supplier. This avoids leakage of unsustainable palm oil to other landscapes and markets. Other examples include Nestlé’s focus on landscape initiatives and the Ferrero ‘Going beyond’ commitment to “explore with our suppliers ways in which we can increase the number of smallholders in our physical supply chain while also ensuring our food safety requirements.“

- Governments in producing countries have implemented more stringent measures to prevent deforestation for oil palm, such as mandatory national certification schemes (ISPO and MSPO) and moratoria on the development of new palm oil plantations in forests or peatland.

- Governments in consuming countries are starting to develop and implement regulatory frameworks that create an enabling environment for producing palm products in a sustainable way, such as the EU Regulation on Deforestation.

- Landscape Initiatives: Both governments and companies collaboratively invested in palm oil producing landscapes to support sustainable agricultural practices, smallholders’ livelihoods, improved land tenure and to protect and restore natural ecosystems. In NI-SCOPS, IDH and Solidaridad cooperate with governments to make producing landscapes “more economically robust and socially just, while protecting and restoring valuable natural resources leading to reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from agriculture and land use change.” Another notable example is the Terpercaya Initiative in Indonesia, where instead of certifying sustainability at the level of individual farms or supply chains, sustainability measures are taken across the region.

This list is not exhaustive and obviously further research is required, but it gives a good representation of the variety of stakeholders that are working to strengthen the movement to stop deforestation.

What’s Next?

It remains to be seen how the future develops. Saving the world’s forest is a global challenge and responsibility. It is great to see that the desire for conservation and the willingness to decrease deforestation is shared globally amongst farmers, companies, governments, NGOs, local communities and workers. To make progress in the pursuit of deforestation-free production, stakeholders in the palm oil value chain have to further intensify their cooperation.

Co-author of the PLOS ONE study Timer Manurung from Auriga Nusantara said that “the slow-down in expansion offers a chance for the Indonesian government and other stakeholders to work together to improve planning and management of oil palm and other plantations. Encouraging good practices and transparency will serve future generations.” The Sustainable Palm Oil Choice fully agrees and calls for all involved parties to collaborate in making sustainable palm oil value chains a reality.

Context on Indonesia and palm oil

Indonesia’s palm oil industry has been closely associated with deforestation, posing significant environmental challenges. The expansion of palm oil plantations has led to the clearing of vast areas of natural forests, resulting in the loss of biodiversity and contributing to climate change. The demand for palm oil, driven by its versatile uses in various products, has fueled the need for more land, often obtained through the conversion of forests. However, efforts are underway to address this issue.

Indonesia world’s largest palm oil producer

Indonesia, as the world’s largest palm oil producer, faces complex challenges with oil palm plantations and palm oil production. The expansion of industrial and smallholder oil palm plantations has led to deforestation and rising palm oil prices. Palm oil production underscores the need for sustainable practices and zero deforestation commitments. However, the impact on forest loss and deforestation risk remains poorly quantified. Efforts to protect natural forests, improve palm oil supply chains, and reduce deforestation risk are crucial.

About deforestation and palm oil Indonesia

Deforestation and the palm oil industry in Indonesia are interconnected issues that have garnered significant attention due to their environmental and socio-economic impacts. Indonesia is the world’s largest palm oil producer, with palm oil plantations covering millions of hectares of land. Palm oil is a versatile vegetable oil derived from the oil palm tree (Elaeis guineensis) and is widely used in various products, including food, cosmetics, and biofuels.

The expansion of oil palm plantations has led to deforestation in Indonesia, particularly in tropical rainforest areas. The clearing of natural forests to make way for palm oil plantations has resulted in the loss of valuable ecosystems, including old-growth forests and species-rich communities. This deforestation also poses a threat to biodiversity and contributes to climate change by releasing significant amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

The palm oil sector in Indonesia has faced criticism for its role in deforestation. Many oil palm concessions, including both industrial and smallholder plantations, have been linked to forest clearing. However, it is important to note that not all palm oil production is associated with deforestation. Efforts have been made by some companies and organizations to adopt zero deforestation commitments and implement sustainable practices in their supply chains. As a result, sustainable palm oil is a much better option.

Regulations to address deforestation for palm oil

The Indonesian government has implemented forest regulations and initiatives to address deforestation, such as moratoriums on new palm oil concessions and the establishment of protected areas. Additionally, there has been a growing recognition within the palm oil industry and the international community of the need for sustainable palm oil production. The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) is a global certification scheme that promotes responsible palm oil practices.

Despite these efforts, deforestation for palm oil remains a significant issue in Indonesia. The demand for palm oil, coupled with rising palm oil prices, has driven further oil palm expansion, increasing the deforestation risk. The European Union, as a major importer of palm oil products, has also expressed concerns about the environmental and social impacts of palm oil production, leading to discussions on potential regulations and sustainability standards for zero palm oil deforestation.

It is worth noting that while progress has been made in addressing deforestation in the global palm oil production industry, the impacts of palm oil-driven deforestation and the effectiveness of mitigation measures remain topics of ongoing research. The complexity of the issue, the involvement of various stakeholders, and the need for robust monitoring and enforcement make it challenging to fully quantify and address the impacts of deforestation in Indonesia’s palm oil sector.

Update data 2024

After 2 years of increased deforestation, in 2024 the palm oil-drive deforestation in Indonesia declined again. Nusantara Atlas reports:

“In 2024, the conversion of old-growth forests to industrial palm oil plantations in Indonesia slowed slightly compared to 2023 (White bars; Figure 1).

Our analysis, conducted using satellite images from Sentinel-2 and Planet/NICFI, reveals that industrial plantations expanded by 117,139 ha hectares in 2024 (White and black bars; Figure 1), a 9% decrease from the previous year. The associated deforestation also declined by 9%, with 31,314 hectares of forest converted in 2024 compared to 34,353 hectares cleared in 2023.”