Critical Oversight: How a Flawed Study Risks Undermining RSPO Certification

Misinformation is rife in our digital world; sometimes it’s harmless, other times it can have negative consequences for efforts that matter. Such is the concern of Meijaard et al. who newly submitted a review to preprint that highlights the fundamental methodological oversight of a recent scientific publication, the conclusions of which suggest that RSPO certification reduces the efficiency of oil palm plantations.

The original study by Nina Zachlod and colleagues investigated whether certification had unintended consequences for Malaysian palm oil, using socioeconomic indices and satellite imagery, finding that activities conducted to gain certification, as well as those of certified estates, led to overall reduced production efficiency. The authors, therefore, called on the RSPO to revise their standards to account for unintended consequences.

While calling for such revisions could result in a major overhaul of RSPO practices and put a question mark against any existing certification, the greater concern is that the publication of this paper, could harm the credibility of the RSPO and discourage further estates and companies from seeking certification.

This concern is amplified by the findings of Meijaard et al., whose new analysis directly contradicts the conclusions of the original study. Their review uncovered that the core claim, that RSPO-certified plantations experience declining efficiency, rests on a misinterpretation of basic agricultural processes. Specifically, Zachlod et al. had interpreted decreases in canopy cover as evidence of lower productivity. However, Meijaard and colleagues demonstrate that these declines simply reflect routine oil palm replanting, a standard practice carried out every 20–30 years. When older palms are removed and replaced, temporary canopy loss is expected, not indicative of management failures or certification burdens.

Figure 1. Oil palm replanting in progress in a plantation on Belitung Island, Indonesia. Photo by Erik Meijaard

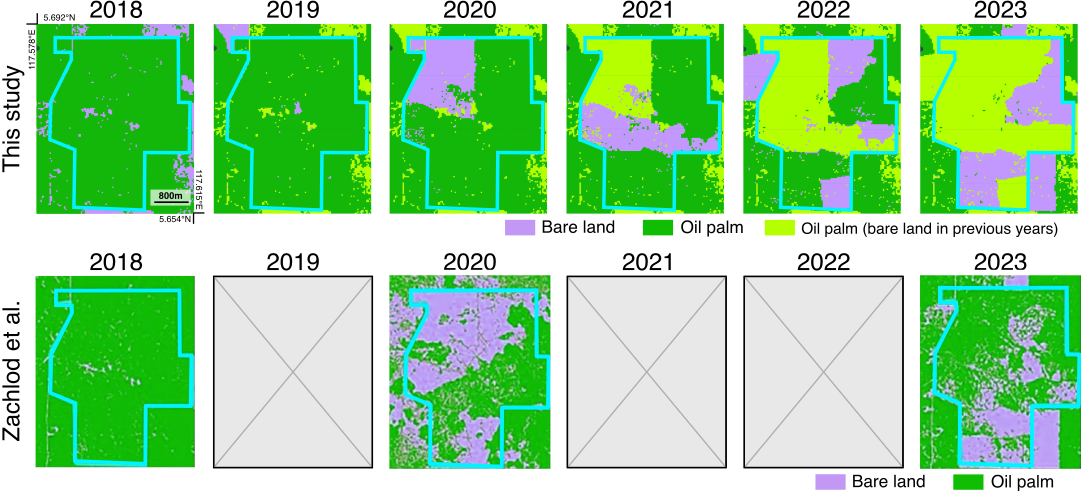

Drawing on data from nearly 94,000 hectares across 102 plantations, Meijaard et al. found that around one-third of the studied area underwent replanting between 2018 and 2023, meaning the very signal Zachlod et al. used to infer inefficiency was actually unrelated to certification. Their analysis also highlights further methodological issues: the lack of appropriate control areas, misapplied statistical models, omission of uncertainty estimates, and the unjustified leap from local observations to global claims.

Figure 2. Comparison of land-cover classification results for a Wilmar plantation certified in 2023. The top row shows results from this study for 2018–2023. Purple indicates bare land, green indicates oil palm, and yellow highlights oil palm replanted on bare land identified in previous years. The bottom row shows the corresponding results from Zachlod et al. (taken from their Figure 4) for 2018, 2020, and 2023.

These errors are not trivial. The original study attracted media coverage, with some headlines implying that sustainability certification harms productivity. Reduced productivity could mean a need for more land to grow oil crops, and the risk of deforestation. Such narratives could discourage companies from pursuing RSPO certification, undermining both market incentives and global sustainability goals. As Meijaard et al. stress, rigorous, context-aware research is crucial when studies have the power to influence public opinion and policy.

By clarifying how methodological oversights led to misleading conclusions, the new analysis serves as a reminder that responsible science is essential, especially when the stakes extend far beyond academia.