Mythbusting: No, Palm Oil is NOT in 50% of Supermarket Products

“Absolutely no palm oil, ever!”

A bold claim, often printed proudly across product packaging. But it’s a largely unhelpful statement that stokes consumer fear without offering a clear understanding of the issue. The impacts of palm oil, like those of any vegetable oil, depend far more on how and where it’s produced than on the crop itself.

Fears surrounding palm oil, and the marketing advantages gained by promoting “palm-oil-free” products, are largely driven by media narratives that focus solely on the negative. These one-sided portrayals often ignore the contexts in which palm oil is produced ethically and sustainably, and more importantly, they rarely mention the environmental downsides of the oils that typically replace it.

For example, one frequently cited claim is that palm oil is found in 50% of supermarket products. You may have come across it before; it has become a staple of anti-palm oil campaigns. Big numbers presented in familiar contexts are powerful tools for shaping perception. Think of the widely used image of “6 football fields of forest lost every minute” (ref). But given their potential to influence public opinion and behavior, such statistics should be grounded in solid evidence.

A recent study by myself and a team of scientists, currently under peer-review, explored this particular claim, originally popularized by WWF in 2006. It didn’t take long to discover that the “50%” figure wasn’t backed by research. The parameters were unclear. Did this refer to global supermarkets? Were only packaged goods included? What about household items, fresh produce, or cleaning supplies?

Assessing all products in all supermarkets across the world would be a stretch for a research team of just five. Instead, we selected a random sample of around 2,000 items across three major supermarket chains in the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Australia as a practical way to test the claim’s validity.

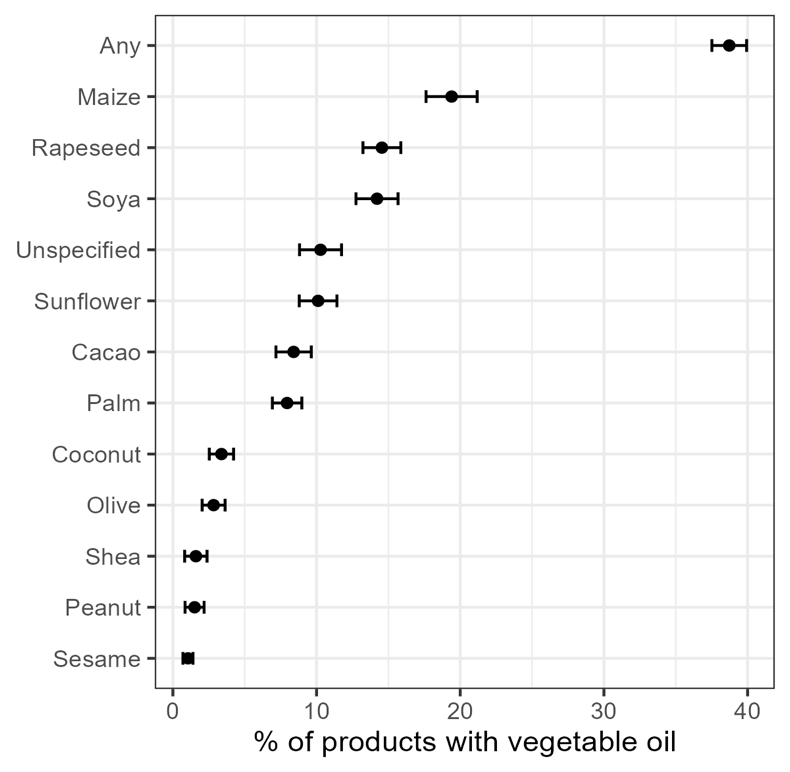

Our preliminary findings are eye-opening. Palm oil was found in far fewer products than the widely cited 50% claim suggests. In fact, oil crops like maize, rapeseed, and soya appeared in more products than palm (Figure 1). Yet, when was the last time you saw a product proudly declare it was free of rapeseed?

Figure 1. Overall Relative Presence of Oil Crop Derivatives

This isn’t to say that palm oil is without its issues or that we should be advocating for its inclusion in everything we consume. Rather, it highlights how palm oil has become an easy scapegoat—singled out by powerful campaigns that have turned it into public enemy number one, while the environmental and social costs of other oils remain largely overlooked.

This study underscores a critical point: the environmental and social impact of any crop—palm oil, soya, maize, or otherwise—is determined not by the crop itself, but by how and where it’s produced. Palm oil isn’t inherently worse than other vegetable oils. In fact, it’s highly land efficient compared to many alternatives. The issue lies in the production practices: deforestation, exploitation, and lack of oversight in some regions are what give palm oil its tarnished name.

Unfortunately, when campaigns present selective or misleading information, they can skew public perception. By vilifying palm oil without context, they may unintentionally endorse its replacements, many of which are just as problematic, if not more so, in different ways. When a product boasts that it’s “palm oil free,” consumers often see that as a moral shortcut. They’re offered a quick and simple choice, and who wouldn’t take the easier option when the narrative feels so clear?

But that clarity is often an illusion. The truth is messy, nuanced, and less marketable. If we truly care about sustainable agriculture and reducing harm, we need to move beyond binary thinking. Consumers must look beyond the label, question the sourcing of all ingredients, and push brands to provide real transparency, whether a product contains palm oil or not.

Sustainability doesn’t come from swapping one logo for another. It comes from understanding systems, challenging simplified narratives, and demanding that all producers of palm, soy, sunflower, or rapeseed be held to the same high standards.

Because if we’re only asking whether a product contains palm oil, we’re not asking the right question.