The issue is where to plant oil palm, not the commodity: raising awareness about trade-offs in landscape management through a digital game

The latest report from FAO, The State of the World’s Forests 2024, highlights that although 4.1 billion ha (31%) of the area in the world’s land surface is still covered by forests and there is a declining trend in global deforestation, forest conversion still occurs. It was estimated that 420 million ha of forests were lost between 1990 and 2020, and most of the conversion in the tropics was for agricultural expansion (FAO 2020). A study estimated that 86% of deforestation was associated with agricultural crop and cattle production (West et al, 2025), and this led to the implementation of the no-deforestation supply chain interventions to contribute to halting deforestation.

One of the targeted commodities in the no-deforestation supply chain regulation and campaign is palm oil, which has created a dispute among producer and consumer countries, as seen in the case of the EU Deforestation-Free Regulation (EUDR) implementation with the Indonesian Government (Jakarta Post, 2025). Despite its controversy, the global demand for vegetable oils is projected to increase by 46% by 2050, with palm oil still the most productive and versatile oil crop (Meijaard et al., 2020).

However, the public perception in the consumer countries towards palm oil is still puzzling—as the study by Lieke et al. (2023) shows that the public tends to have negative views on palm oil due to its associated environmental impacts—however, the public misses that the real problem is why the impacts have arisen, which is when the oil palm was planted through conversion of forests. The public has limited understanding that this can happen with other commodities, and larger trade-offs can happen with less productive oil crops (Lieke et al. 2023, Meijaard et al. 2020). The perception of the public consumers is important because our study suggests that green consumer behavior in consumer countries is indeed influencing sustainable governance in the producing countries, as the majority of the oil was exported to the global consumers. On the other hand, stakeholders in palm oil-producing countries have come to understand that a sustainable product is defined as one that is no-deforestation (Purnomo et al. 2024).

CIFOR-ICRAF promoted the landscape approach, which is defined as allocating and managing land to achieve and align with landscape sustainability goals (social, economic, and environmental) (Sayer et al. 2013). This approach has evolved with various interpretations for various contexts, including agricultural commodity production. The Landscape Approach principles recognize multiple stakeholders and their interests in the landscape. Different interests of stakeholders in the landscape (e.g., conservationists, commodity producers, and consumers) led to complex governance; thus, improving understanding of the stakeholders will help an inclusive co-production process in the landscape management, and that is why the knowledge transfer and education process is important in the implementation of the landscape approach (Reed et al. 2020).

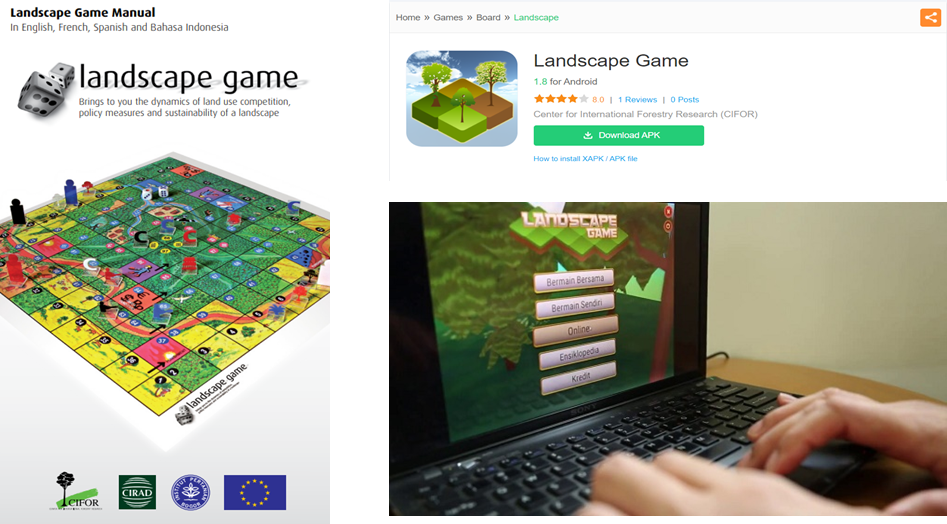

CIFOR-ICRAF and partners developed Landscape Game 2 in 2024, that aims as a learning tool to understand about dynamics in landscape management and balancing conservation and development. The early version in 2007 was launched as a board game and produced for more than 1,000 copies. Due to high demand, the digital version was developed in 2014 to accommodate wider use (Figure 1). The first version of the game often use in the brainstorming process for the workshops and shows that the game play can influence player’s mental model that improve the complexity of landscape management (Purnomo et al 2017). To advancing the player experiences, the second version was launched in March 2024 with adopting experiential learning as landscape manager and add component on commodity trade – to enhance user experiences (Figure 2). Later, the second version of the Landscape Game, developed into digital experiential learning tool that not only use for stakeholder capacity building – but also in education.

Figure 1. The first version of the Landscape Game

Figure 2. Landscape Game 2, can be downloaded in https://www.landscapegame.org/

The landscape game is designed as a multiplayer game, and four players will compete on land management within a landscape. A landscape is assumed to be 225,000 ha and consists of 225 small patches of 1,000 ha. Four players will compete to manage several land blocks in the landscape, from obtaining the land until trading commodities (products and services) produced from the management.

The type of land block is following the landscape concept by Chomitz (2007), which divided landscape into three types, and each type provides different ecosystem service potential and utilization options (Figure 3). There are “forest core,” “forest edge,” and mosaic land. The player can choose several management options, such as conserving it but getting carbon credit; developing ecotourism along with conservation; or converting it into crop yield, mining, or ecotourism.

Figure 3. Type of landscape in the game, follow concept by Chomitz (2007)

The common goal of the game is to keep the balance between the environment and economic status of landscape management, measured in the game by landscape goal indicators, carbon credit, land productivity, and economic benefit. All actions of players in the landscape influence these indicators. The game has threshold to keep the balance condition in the landscape, and if the environment indicator (carbon credit) is below the threshold, then the disaster will occur and reduce the commodity production in the landscape. At the end of the game, successful landscape management is achieved if the environment and economic status of land are balanced—by keeping carbon credit and one of the economic indicators above the threshold (Figure 4).

With this gameplay, the player can understand more the concept of trade-offs between environmental conservation and commodity development in landscape management – and become more aware that the key problem of oil palm is not the type of commodity but rather the production process in the landscape. Almost two years after its launch, the Landscape Game 2 has been played by more than 1,000 users around the world, mostly by youth. The developing process also engaged youth, including in the testing (Figure 5). The game engaged with global audiences by providing seven different landscape to play: Forest City, Peatland, Java, Congo, Pacific, Borneo, and Brazil (Figure 6).

Figure 4. The landscape status influenced actions of the players and measured through three indicators (environment and economy) and when the environmental indicators below threshold, players will learn about consequence through occurrence of disasters.

Figure 5. Landscape Game testing involved youth

Figure 6. The landscape selection in the game play

References

FAO. 2024. The State of World’s Forest 2024. Accessed in https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/ec487897-97b5-43ec-bc2e-5ddfc76c8e85.

FAO. 2020. The State of World’s Forest 2020. Accessed in https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/ca8642en.

Chomitz, KM., 2007. Overview – At Loggerheads? Agricultural Expansion, Poverty Reduction, and Environment in the Tropical Forests. The World Bank. Accessed in https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/70144056-735a-5cce-9367-2646669f305a.

Lieke, S.D., Spiller, A. and Busch, G., 2023. Can consumers understand that there is more to palm oil than deforestation?. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 39, pp.495-505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2023.05.037

Meijaard, E., Brooks, T.M., Carlson, K.M., Slade, E.M., Garcia-Ulloa, J., Gaveau, D.L., Lee, J.S.H., Santika, T., Juffe-Bignoli, D., Struebig, M.J. and Wich, S.A., 2020. The environmental impacts of palm oil in context. Nature plants, 6(12), pp.1418-1426. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41477-020-00813-w

Purnomo, H., Kusumadewi, S.D., Ilham, Q.P., Kartikasara, H.N., Okarda, B., Dermawan, A., Puspitaloka, D., Kartodihardjo, H., Kharisma, R. and Brady, M.A., 2023. Green consumer behaviour influences Indonesian palm oil sustainability. International Forestry Review, 25(4), pp.449-472. https://doi.org/10.1505/146554823838028210

Purnomo, H., Shantiko, B., Wardell, D.A., Irawati, R.H., Pradana, N.I. and Yovi, E.Y., 2017. Learning landscape sustainability and development links. International Forestry Review, 19(3), pp.333-349. https://doi.org/10.1505/146554817821865027

Sayer, J., Sunderland, T., Ghazoul, J., Pfund, J.L., Sheil, D., Meijaard, E., Venter, M., Boedhihartono, A.K., Day, M., Garcia, C. and Van Oosten, C., 2013. Ten principles for a landscape approach to reconciling agriculture, conservation, and other competing land uses. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences, 110(21), pp.8349-8356. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1210595110

The Jakarta Post. 2025. WTO favours EU over Indonesia on palm oil restrictions. Accessed in https://www.thejakartapost.com/business/2025/01/11/wto-favours-eu-over-indonesia-on-palm-oil-restrictions.html.